The essence of my work, that which I have written and spoken about the most, is that I believe the future of humanity depends on individuals and society evolving beyond, and being liberated from, identification with ego. I say liberated from, because I see that this identification has the characteristics of an addiction that, like a chemical addiction, keeps us functioning destructively, while in denial of the consequences. This cannot continue without, again, like a powerful chemical addiction, lethal consequences. I see humanity at an evolutionary tipping point. Our social structures, our religions and our psychologies cannot take us into the future unless a fundamental evolutionary step beyond identification with ego is taken.

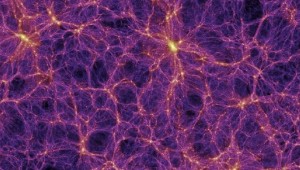

We must realize that while ego, with its compulsion to competition, invention and domination has been the driving center-piece of human history, in fact, our proudest characteristic, it is also our blind-spot. It is the fatal flaw that separates us from the truths upon which this Universe operates, the truths of interconnectedness and wholeness. It is these truths that we must realize and embrace if we are to achieve real sanity, both as individuals and as a species. In fact, the realization and adoption of these truths are essential if species Homo Sapiens is to survive into the future with any quality of life.

Humanity’s failure to question its identification with ego-based motivation and functioning has created the social order as we understand and live it today. It has created the social institutions, philosophies, economies, populations and technologies that now are the reality of human existence on the planet Earth. What we seem blindly oblivious to, is that these givens also threaten the very eco-system that humanity’s quality of life, and perhaps, its very survival, is dependent upon. Before it is too late, we must face the limits and dangers of this perspective. As with all species, when faced with crisis with its environment, we must evolve, or die out. The question is whether we will evolve to accommodate these new environmental realities, accepting and adapting to a deeply diminished quality of life, or whether we will evolve a consciousness that can reclaim life as beautiful and balanced.

Symptomatic of the error of the egoic perspective has always been the unique personal emotional suffering that humans experience, different from any other species. Our unique capacity for abstract reasoning takes the information of our senses and tells us that we are alone and insignificant, and creates a psychological construct of that isolation called the ego. The ego experiences this isolation and responds with anxiety, and from this fear-based emotion, we do terrible things to ourselves, others and to the planet in endless compulsive schemes seeking to create significance for ourselves. At every level of human organization, from the individual, through families, communities and societies, this curse has haunted human history, and we have run out of answers. Religion doesn’t work, psychology doesn’t work, politics doesn’t work. We have created a competitive, insecure, consumption oriented world culture that is consuming the planet, but first, it has consumed our sanity.

All the great mystical religious prophets have seen this deep truth and the decoding of their teachings always tells this story, from the ancient Hindi, Taoist and Buddhist texts through the Biblical Garden of Eden, through Jesus and Mohammed, but ego is a slippery character, not very principled, and has always managed to take spiritual insight and twist it into religious dogma that serves ego, not God, or man. Ego will use any rationalization to continue its self-absorbed, self-indulgent and delusional ways, and so, the evolution beyond egoic orientation, for individuals and for humanity, requires a willingness to enter into some very dedicated commitments.

In this exploration, I will focus on the individual dimension, and the path that leads to individual evolution into a deeper sanity. The planetary journey I advocate must, of course, begin with individuals, for the evolutionary success of any species begins with adaptations accomplished in individuals. A deeper understanding of the achievement of individual sanity and consciousness has to be the beginning place for planetary evolution. It is my hope that with a growing evolution within individuals to higher consciousness, what has sometimes been called a “critical mass” of individuals can be achieved, carrying forward the principles of interconnectedness and wholeness for the species.

*

I choose to call the required commitments “radical” because the term radical implies to take something to its root, to return it to its source. This source is the true potential for human beings. Radical also means to seek fundamental change with deep fervor. To penetrate and overcome the overlay of false identity and values that has been the human path since civilization began, no doubt, requires a sincere and conscious effort, and any person who seeks to break through this addiction to ego will discover that they are dealing with a powerful force that continuously pulls them towards unconscious conformity.

To alter this deeply ingrained orientation, this false belief in and addiction to egoic aggrandizement, will require a fundamental reorientation; a breaking of the worshipful attachment humanity has for ego, for specialness and superiority. It will require a reclaiming of humanity’s roots, its origin in a Nature that is a harmonious whole. This, however, is not easily accomplished, for we cling tenaciously to this patently destructive orientation. We turn a blind eye to the unending damage this false sense of entitlement brings in every arena of life. We are in total denial.

This realization I am speaking of is not new. It is as old as humanity. It is the reason that along with social and technological development, a counterbalancing force has always been present in the form of spiritual and religious prophets, warning us against this “devil” within us. Of all the religious traditions, however, I believe that Buddhism has managed the clearest insight into what is not only the fundamental spiritual dilemma of humans, but also the source of their basic psychological conflict. Within Buddhism, it is my belief that there is one manifestation that has stayed the truest to the psychological nature of the teachings of Buddha, and has consciously avoided, as did Buddha himself, overlaying its insight with theological content. That is the Zen tradition.

Zen masters understood the conundrum of confronting the deeply conditioned pull to socially sanctioned egoic perspective in constructing Zen training historically as strenuous, rigid and hierarchical. It required the student to demonstrate to the teacher repeatedly the depth of their commitment to the discovery of enlightenment, their “true face.” Zen training was designed to create the psychic tension necessary to break through cultural conditioning to identification with egoism. It was a strenuous rehab program in kicking the ego habit and becoming a free human being.

In a kind of cultural judo, Zen training used the cultural conditioning of traditional Asia that stressed conformity, hierarchy, discipline and obedience to break the hypnotic hold of the main culture. The student’s cultural conditioning towards unconscious self-absorption and cultural conformity was strenuously challenged, then supplanted with a dedication to Zen principles, practice and culture. The judo was in using Oriental culture’s conditioning toward obedience and conformity to create a breakthrough into independent, non-egoic, even transcendent, thought and action.

It is my belief that modern seekers do not necessarily require the coercive rigors of traditional Zen to make this breakthrough, as moderns have a much greater inclination toward independent thought than did the people of the traditional Asian cultures. I believe this inclination toward free thought and action can be harnessed, again in a kind of judo, to see through the false promise and hidden conformity that the Western cult of materialistic, egocentric personality has conditioned into us. I believe, however, that while it is appropriate to marginalize the oriental cultural trappings of Zen training, the Zen tools of disciplined meditation, mindful action, compassion and koanic thought remain essential in this journey toward freedom. They are the skills that must be practiced to develop the discipline of mindful awareness that acts as a counterbalance to egoic mind.

Egoic orientation is based on living “religiously,” that is, in believing to be true that which only has its dogma as its proof. The antidote to this dogmatic unconsciousness has always been, and will continue to be, training in shifting identity from one’s cultural programming to conscious awareness, observation and embracing of life-as-it-is. As the Buddha taught, a seeker ought to believe nothing, using the teachings (dharma) only as a guide that leads to a direct experience, an enlightening, concerning not only the world and society, but also the workings of mind itself.

The practice requires that we give very present and mindful attention to both our internal mental world and the world around us. It is to shake off the hypnotic hold of cultural egoic conditioning that tells us who we are, what life is about, and what is possible. It requires a disciplined effort to expand the contours of awareness, for it is as the great psychologist Fritz Perls used to say, “The contours of our neurosis are the same as the contours of our awareness.”

I look to five fundamental dimensions of life, which when examined and practiced with a sense of radical commitment, can be a path opening our awareness to the truth of life, and can expand the contours of our awareness and thus, our sanity. I suggest that a powerful path for personal growth is to bring into our lives a radical commitment to truth, presence, compassion (empathy), gratitude and peace. I know that when these commitments are practiced with dedication, they will, without question, lead the way, shepherding us on the path to personal liberation from the insane trance of ego.

These commitments are not new in themselves. They are distilled from such classical Buddhist teachings as the “Four Noble Truths”, the “Eightfold Path” and the “Three Gems of Refuge”. In my quest to bring a contemporary approach to teaching the path of conscious and liberated living, I have sought to identify how I have personally synthesized, condensed, contemporized and blended these classical teachings with other influences. The Five Radical Commitments are my way of pointing out this path, that the East calls, “The Way”.

*

THE RADICAL COMMITMENT TO TRUTH

To be committed to radical change, to the evolution of our lives into deeper sanity and wisdom, has to begin with a commitment to the truth. Note that I didn’t write that with a capital “T,” because “Truth” seldom represents the truth. When we seek to find truth we can only be committed to the ever-flowing experience of what is, and “what is” is never static. Capital T “Truth” is dogma. It insists that it is the culmination of experience, and so, has nowhere to evolve to. It never changes (until it does). It is what you are told to believe. It is what society says is so.

The truth of your life, however, is something you cannot be told. Several years ago I wrote a book of poems inspired by the Tao Te Ching, and in it, one of the lines reads, “I can tell you my truth / but I can never tell you yours.” Each person’s search has to be for their own truth and no one else’s. Most of an enlightened person’s truth will look like everyone else’s, and that’s OK, it even has to, because the collective cultural truth is contained in what is. The enlightened person’s truth will contain a significant element of their culture’s truth as well, but only because they have given consideration to it and decided for themselves that it is at least harmless to share this perspective with others. The difference between an enlightened person’s truth and the cultural truth is probably less than 10%, but oh, what a 10%.

The search for truth is so important in the quest for conscious living that Buddhism begins with the teaching called, The Four Noble Truths. In them, the Buddha identifies the ego as the source of human suffering, and he is so certain of this, that he identifies this teaching alone amongst his teachings as Truth. The interesting thing about the Buddha as a religious prophet is, that as soon as he gave us the “Four Noble Truths”, he also said we were not to believe him. I don’t know of any other prophets who said anything similar, and usually, quite the opposite on pain of damnation. But Buddha told us to experience for ourselves, because that is what he had done. He said that he could share his personal experience of truth and how he arrived at it, but for each person, their own personal experience was the only way. Enlightenment isn’t a teachable concept. It is only an experience-able concept. This is Zen.

Truth must be a choice. It must be what a person freely chooses out of their own experience. Any point of view not apprehended from personal conscious penetration into the experience of life is dogma. It cannot be truth. Siddhartha Gautama’s search led him to an awakening. He awakened out of the sleep of programmed egoic mind into a more primary awareness, the awareness of his true self and potential. It is always important to keep in mind that the name “Buddha” given to Siddhartha simply means “awakened,” not God, savior or prophet. He disciplined himself to shake off entirely the lazy mind that cultural programming tells us to experience life from. He came to be fully without what he called “illusion,” that is, what you think to be true without personally knowing it to be true. He realized that the mind of ego is made of mental representations, mental forms that create the conceptual boundaries and limits that we experience to be our lives. The ego also places veils, made of these mental forms that are conditioned into us over our ontological eyes, and it is these veils, these “illusions,” that stand between us and the truth of what our lives can potentially be. These veils stand between us and our true self, and our one true purpose. The Buddhist path of mindfulness has as its purpose, to support us and guide us while we look deeper into our lives, to discover a dimension of truth that has heretofore eluded us.

When the journey to “awakening” is chosen, it must always begin with a fearless examination of what in our lives is actually true and what is only believed to be true because we are conditioned to hold it as true, these, our “illusions.” We must also be willing to face what truth we are in denial of, and what truth we are in defiance of. Our suffering, as the contemporary prophet, Eckhardt Tolle, says, is in our resistance to what is, and aware presence and questioning leads us to the realization of what another great prophet once said; “The truth will set you free.”

How very unique was Buddha’s declaration, “Do not believe me, experience for yourself.” How powerful! How true. All other religions insist in blind belief. Buddhism only says, open your eyes. Look through the veils that cover your mind. Religion is one of these veils. So is society. An aspect of truth is that any belief system that is an “’ism” is such a veil of illusion. Even Buddhism. Where Buddhism is taught as dogma, it is no different than any other competing belief system. Somewhat amazingly, however, Zen Buddhism also teaches, “If you meet the Buddha, kill him.” Maybe you’re beginning now to get some idea of the meaning of this most puzzling of koans.

Each human being has an egoic personality created by a combination of genetic pre-dispositions, personal experiences and the cultural influences of their life. Our grave error is in confusing this egoic programming for who we are, and what it tells us to be the truth. The commitment to truth requires of us only to be aware and to look deeply. It tells us that each moment of our lives is a moment we can choose to remain blinded by the veils of mind, or to peer into and through them asking, ”what is the unique truth of this moment, this situation?”

This truth will be recognizable when we learn to still our talking, judging, fearful and limited egoic minds. This truth will be evident when we experience the substantive difference an encounter with deliberate and open consciousness brings. The only real instruction of Buddhism is to open your mind. Search for the awareness that tells you the source of who you are, free of cultural and personal conditioning. This is the most fundamental of The Buddha’s teachings. It is his truth that he offers, while he also instructs you not to believe him, to experience it for yourself. He offers through the skills of meditation and mindfulness the path that can lead you. Learn to still your egoic mind. Learn how to not be blindly directed by its whispers, murmurs monologues and shouts, telling you who you are and what is happening. Instead, learn to be present for what actually is happening. This simple but vastly challenging perspective is what the Ancients called enlightenment.

*

THE RADICAL COMMITMENT TO PRESENCE

“This moment, what is lacking?” – Zen Master Rinzai (9th Cent.)

To live in our truth requires of us that we also be fully present. If we are to stand any chance of finding our truth, we must begin by being fully present. Otherwise we are always projecting the preconceived notions of our conditioned mind onto the situation. Our truth cannot be found in this manner.

Truth is never static. Full presence is required in fulfilling the commitment to truth because only through being fully present are we able to recognize what the moment needs from us. Only through being fully present and receptive to the “is-ness” of the moment can we know best how to be in harmony with the moment, as it is. Truth can only be found in the ever-flowing experience of what is, and truth can only be experienced through being at one with what is. Do you get it? “What is” exists only in the moment that it is. It cannot exist anywhere or when else.

Rinzai’s Zen is reflected in the realization that truth and enlightenment are only found in comprehending the perfection of the moment. This moment, the only thing that can be lacking is our full presence, our awareness uncompromisingly engaged with the moment recognizing the truth and perfection of this moment. Our task is never to assume it or take someone else’s word for it. We must find it on our own. Otherwise, we only have our projection of truth as it has been conditioned into us. We only have the doctrine of our lives, static and full of conditions for what we hold as necessary for our satisfaction.

This is the lesson on human suffering contained in the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths. When we penetrate this lesson with its teaching that human emotional suffering is caused by our grasping after life being the way our egoic selves expects and wants it to be, we find that we actually live our lives not very present for life at all, not being a witness to the “is-ness” as it is. Rather, we live projecting onto life the drama of our expectations and desires. Our emotional suffering results from the realities of life not fulfilling these projected wants and from our being confronted with what we don’t want. Buddhism refers to this cosmic tail chasing as the wheel of suffering, lifetime after lifetime, chasing after illusions. But Buddhism is a religion of salvation because the Buddha taught that there is a way out of this suffering, and it is through the embracing of life just as it is.

We live our lives focused on our desires, fears, victories and frustrations. We measure every moment by whether our desires are being fulfilled or frustrated. We mostly live seeing the world only as a projection of this drama. We are unable to be fully present and resourceful for the world being exactly as it is. We become increasingly self-absorbed, cutting ourselves off from the “what is” of life, as reality doesn’t conform to our expectations. We increasingly live in the dogma of the “Truth” of our socially programmed egoic perspective, resisting all occurrences and situations that do not concur with this Truth.

This state of emotional protest is the undeniable source of our suffering as individuals and as a collective. It is always marked by the withdrawal of our full awareness and resources from engaging the moment as it is, but rather living in compulsive thoughts and behaviors about the way we are programmed to believe things are supposed to be. We become neurotic, doing, from our unconscious programming, the same thing over and over again expecting different results. It just doesn’t work, but our ego cannot accept that it doesn’t work.

Then, we resort to not being honest that things just keep getting worse, or, at least, not much better. We live in a state of denial. To back up this dishonesty, we compound our error by not allowing ourselves to be present in a profound way, in a way that might cause us to see how our expectations do not fit with the truth of the moment. We conspire within ourselves to be neither honest nor fully present.

The great psychologist, Fritz Perls, used to note that, “neurotic thinking is anachronistic thinking, out of place in time.” We live our lives with our mental focus either on the past, clinging to the story of our lives, or in the future, projecting our envisioned successes or dreading the challenges to our significance and success. Perls noted that we rarely have all our energies focused on the place and time where our lives are actually lived, in the here and now, the only place where true sanity and effectiveness can be found.

Each moment of our lives is an opportunity, grasped or missed, to be truthful in our lives. To be truthful then requires of us to be mindful, to be fully present. This moment, the only thing that can be lacking is our focused attention, our full, unadulterated presence. Over and over again, remind yourself of this, and with the reminder, sharpen your focus into this moment as it unfolds, just as it is. There, the secrets of life, of your life, will be revealed. This present moment, fully engaged, is the doorway to that mysterious quality we often see in people that we find compelling and charismatic. It is, as expressed in one of those amazing double entendre words that describes both the behavior and the result, having “presence.” This moment, find truth, clarity and presence. Then, nothing will be lacking, and as the Buddha taught, the path that brings an end to suffering may well begin to open before you.

*

THE RADICAL COMMITMENT TO GRATITUDE

A Zen master was walking through a forest when a tiger began to chase him. He ran, but his escape was cut off by a cliff over a deep chasm. He saw, just within reach, a root growing from the cliff that could hold his weight. He scrambled down and was dangling from the precipice with the tiger above him, certain death below. A rat came and began to gnaw at the root. Soon, it would no longer hold his weight. He noticed a berry bush within reach, too small to hold his weight; he picked a berry and ate it. His mind filled with the thought, “How sweet tasting this berry is!” – Traditional Chinese Zen story

So far, I have written about embracing the idea of living from commitments to truth and presence as guiding principles on the journey to personal peace and effectiveness. These guides, however, lead to an important question; what if the truth of the present moment contains what is terrible and frightening to us? What if in the truth of the moment, as in the above story, is our destruction? What if it contains terrible physical pain? What if it contains losing what is highly valued, even precious to us? These are the circumstances that Buddha’s teachings were specific to. It teaches that our suffering is in our resistance to what is, what Buddhism calls “attachment,” and that the end to suffering is in opening and embracing what is, what Buddhism calls “non-attachment”. This sounds wise enough, but how can we follow this instruction when “what is” contains our worst nightmare?

Those who choose to follow the Buddhist path, or, for that matter, the path of Jesus, Judaism or the Prophet Mohammed, are faced with this quandary. How can we realistically live our lives and follow the Buddhist path of non-attachment, or the Judeo-Christian-Islamic path of “Thy will be done”? Contained in this quandary is the essence of spiritual teaching, for it is here that we discover that this path teaches us that we live in two dimensions; the egoic dimension, which is the psychological correlate to our experience of physical separateness, and also, in the ultimate, or spiritual dimension, where the unity and perfection of Creation is absolute.

In the egoic dimension, we attach to safety, comfort, pleasure and status. There is nothing wrong with this, but, as Jesus said, “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of Heaven,” meaning that attachment to the material blocks the way to the spiritual. We must know when to let go of the egoic, the material, and embrace life just as it is in its manifesting perfection even when, at that moment, life’s circumstances are being harsh on you. We must know when attachment to our preferences and perceived needs has turned to suffering. We must know when to release our grasping nature and return to non-attached embracing of life-as-it-is.

The tiger story is instructive because in it, the man does not surrender his life to the tiger. No, he runs from the tiger. Nor, does he quit his fight for life when confronted with the cliff. He surveys the situation, employs his resourcefulness and finds a possible escape in hanging from the root outside the reach of the tiger. The Zen master is not passive. He is not non-attached to continuing his life. He does what he needs to.

The story shifts dimensional perspective, however, when the man runs out of choices. Here, instead of being consumed with horror by his impending fate, the enlightened man shifts into the ultimate dimension. Only this moment exists and all is perfect just as it is. Instead of horror, he experiences gratitude on the humblest of levels. At the moment of his impending death, he allows his awareness to be filled not with horror, bitterness and resentment, but rather with gratitude for the sweetness that he knows with certainty that life also contains.

The Austrian Jewish psychiatrist, Viktor Frankl discovered, while in a Nazi concentration camp, the life and death power this choice can have. Like the man faced with death by tiger or falling, those in the concentration camps had their fates taken nearly completely out of their own hands. All that was left to them was the manner and attitude they could bring to the fate that awaited them. Frankl discovered that how a person approached their seemingly hopeless fate was a determiner of their ability to mentally survive in a circumstance that had already taken everything they valued and gave very little hope of physical survival. He discovered that those who somehow managed to still find gratitude for the simplest of life-affirming experiences stood the best chance of surviving, both physically and psychologically.

Our everyday lives are generally not filled with such impending catastrophe. They are filled, however, with endless choices to focus into what frustrates, frightens or displeases our ego, or to be present for the beauty and perfection contained in Creation. We all know which choice our culture has conditioned into us. There is a Zen saying that enlightenment is easy for the person with no preferences, but what our tiger story instructs us is, that life is made up of endless choices that could be called preferences, even for the enlightened. Our story tells us that when we are fully present, and we seek the complete truth of any moment, the enlightened preference and choice will always contain gratitude.

Every moment, life presents us with reasons to be in resentment or in gratitude. The quality of our life is in the choice we make. This is as important a truth as I know. Every moment, whether it is a mundane moment or a critical one, we have a choice to create heaven or hell for ourselves by shaping our experience around gratitude or resentment. What a liberation it is to know that we can choose to taste the sweetness of the berries and of life.

*

THE RADICAL COMMITMENT TO EMPATHY

The Dalai Lama, when asked whether he hated the Chinese for occupying his native Tibet and driving him into exile, answered, much to the wonderment of his questioner, that he did not. The questioner then asked, how that could be? The Dalai Lama answered that the Chinese “had taken everything from us, should I let them take my mind as well?” He went on to say, he could not hate the Chinese, because they were people just like everyone, who only wanted to be happy, but did not know the proper way to achieve happiness. Their society had conditioned them to seek happiness in a way that created misery for others, taking what did not belong to them. He saw them not as evil and worthy of his hatred, but rather, he saw them as deluded and worthy of his compassion.

What an astounding and instructive answer! The reason that the Dalai Lama does not hate the Chinese is because he possesses a radical commitment to empathy. He is capable of experiencing kinship in the human condition with them. In Buddhism, the concept of compassion is not about feeling sorry for someone as Webster’s Dictionary describes it, but rather, it is about experiencing identification with them. It is an awareness that tells us that in another person, but for circumstance, there would be my life. Ultimately, the Dalai Lama’s insight contains the further understanding that the benefactor of his magnanimous attitude was not solely the Chinese, but really, himself. Anyone who sees a picture of the Dalai Lama knows that this man is an embodiment of achieved happiness and well-being. What the Dalai Lama is telling us in this story is that a very important part of this capacity for profound well-being is in not surrendering our minds to violent emotions.

Why do we have violent emotions that rob us of our minds? Buddhism has known the answer for several millennia. It is the same reason that, in the Biblical tradition, caused Adam and Eve to be banished from Eden. Human ego. Adam and Eve ate the fruit of knowledge of good and evil (judgment), and experienced shame, causing them to hide from God because “they were afraid.” Central to the human experience is a sense of separateness and vulnerability causing us to feel insignificant and afraid. We are compelled to fill our lives with seeking ways to feel more significant and less vulnerable, most of them, deluded and harmful. This is from ego. We behave destructively, or selfishly, or cravenly only because we are afraid. We are alone and vulnerable, frustrated in our desires for perfect happiness. We are afraid that we can never actually be enough.

Compassion is in the living recognition of this dilemma that every person faces, and in understanding that their attitudes, beliefs and behavior stem from this fear. A good place to begin this practice is with those we are close to, but are often caught in a circle of pain with. The Dalai Lama tells us, however, that compassion is measured not in our ability to identify with the sins and suffering of family, friends and those we can easily identify with, but ultimately, with those who, in the circumstances of life, are cast as different than ourselves, even as our enemies. This, of course, was the central spiritual teaching of Jesus as well.

How short of this teaching we fall as individuals and as a society. We live in a society that is described as the “opportunity” society, where the unspoken ethic too often seems to be, “I have to take care of me and get mine, and if necessary, the hell with everyone else”. This ethic emanates from the same deluded mind-set as the one that has China or any other people invading its neighbor to take what does not belong to them, or in feeling that our race, religion, class or country of origin makes us superior. This ethic says that our highest interest is in seeking our own happiness through pride, riches, power and entitlement. This is the ethic that will result in our taking what does not belong to us, in doing harm to others. But as the Dalai Lama points out, we gain nothing. We only lose our minds.

Radical empathy is an important basis for strengthening spiritual and psychological health. It is an aid in moving us beyond complete identification with our small and greedy egoic minds. It is as simple as this: In encountering others, approach them with an open mind and curiosity. Seek to understand and feel what it must be like to be them. Seek to understand life from the perspective of their unique circumstances. Wonder to yourself what life would be like if you had the body, mind and experiences of their life. Know that, just like you, they are doing the best they can with what they have and what they know, and that, just like you, they only want a life that is happy and free of pain. Know that their basic problem is the same as your basic problem, that they only want to feel safe and significant, but that they very often don’t know how to achieve it without doing things that are harmful and foolish. Just like you.

Jesus said, “Judge not, lest ye be judged”. Buddhist compassion lends keen insight into this koan, this finger pointing toward enlightenment. To judge others is to ensnare ourselves in the prison of judgment that separates us from Eden, from our true, sane and compassionate self. The door out of this prison is in looking deeply into Life and the lives of others, seeing the connectedness of everyone and everything. Our failure to comprehend deeply the interconnectedness of life is the source of our “sin”, and is what allows us to do thoughtless harm. Our egoic nature is the serpent.

I am not saying we ought to try to rid ourselves of ego, only tame it. Ego is as much in our nature as spirit, and we live in a society constructed around egoic concepts and interaction. We cannot function without the boundaries of judgment that ego creates, giving shape, form and definition to life. It is, however, important to remember that every judgment we create takes us further into the delusion, further into “the fall” of separateness and fear. I only suggest that we be mindful that the judgments created by egoic mind are best engaged sparingly, and with the warning that they may well be injurious to your spiritual and mental health. They may even take your mind.

*

THE RADICAL COMMITMENT TO PEACE

“If you have not linked yourself to true emptiness,

you will never understand the Art of Peace..

Empty yourself and let the Divine function.”

– Morihei Ueshiba –

Morihei Ueshiba is the Japanese martial artist who developed the philosophy and techniques of Aikido, the “Art of Peace,” the martial art built not around punches, kicks and throws, but of skillfully stepping out of the way of attacking aggressive energy and non-harmingly moving an aggressor to a neutral and harmless place. Its purpose is not to defeat an opponent, but rather to defeat the aggression in the attacker. To do this, we must, of course, first defeat the aggression within ourselves. The “emptiness” that Ueshiba is exhorting us to is a place that is free of ego with its desires to dominate and defeat others. Doing harm is the result of ego’s desire to be right, powerful and significant, usually through diminishing, using and defeating others (or sometimes, perversely, ourselves). Ueshiba is telling us that when we link ourselves to true emptiness (egolessness), we have arrived at the place where the “Divine” in us can function and where harm-doing ends. No aggressive emotions or actions are generated in a mind free of egoic identification. This is the Art of Peace.

Ueshiba describes violence, physical or mental, as energy out of balance, and the way of Aikido is to cultivate harmonious energy within oneself, so that when violent energy is confronted, peaceful energy meets it, blends with it, and turns it, neutralizing the violence. As Ueshiba once said, “There are no contests in the Art of Peace. A true warrior is invincible because he or she contends with nothing. What is to be defeated is the mind of contention within.”

The story of the Dalai Lama’s astonishingly peaceful attitude concerning the Chinese people, despite their invasion of his Tibet, and his response that he did not hate them because although they had taken everything from him, he was not about to also let them take his mind, is the essence of the commitment to peace. It is not solely for the benefit of others, although all benefit. It is first of all for the achievement of a personal inner peace.

*

I have chosen the attributes for radical commitment as I have because, ultimately, personal peace is the place of both psychological and spiritual well-being. I have created a circle. To find personal peace we must be willing to face the truth of the “what is” in any situation, and the more difficult the situation, the more important it is that we face the whole and complete truth. To find the truth, we must cultivate the skill of being truly and deeply present, not fleeing into our preconceptions, prejudices, fantasies, wishes, expectations, projections and fears. Also, to be at peace in any situation, we must be able to find the kernels within the situation that can bring us to gratitude, so that our ego doesn’t fly into fear and see itself as a victim, and finally, to be at peace requires that we develop compassion and empathy so as to deeply understand others, not taking offense or seeing them as enemies. If, as the spiritual teacher, Eckhart Tolle, points out, our emotional suffering is in our resistance to what is, we must be willing to be committed to truth, presence, gratitude and empathy in order to grasp the “what is” of the situations of our lives. The final commitment then must be to sincerely seek to make peace with “what is”.

Through this writing, I have shared my philosophy, based in Buddhist teachings, of personal healing and transformation through the practice of living in radical commitment to these five attributes, and while this may seem like an admirable ideal, I know you must be asking, in the reality of our lives, is this even possible? My personal attraction to Buddhism is because it teaches us that it is, not in an abstract theology, but in a deep and practical psychology. I also see the results of this perspective in the lives of persons like the Dalai Lama and Thich Nhat Hanh, these persons of radiant mental health and spiritual depth.

Yes, you might say, but they are Asian, born to this tradition, living their entire lives as Buddhist monks. What about an American who lives an ordinary American life? Are these not just ideals, like the lives of Jesus and the Saints? Inspiration, however, is not only to be found in these holy personages, but also from the likes of Eckhart Tolle, Ram Dass and other Westerners who have taken this Eastern wisdom and found personal freedom and peace through integrating it with American culture. They see and embrace that they are Western. They also see that to be Western is to be deeply embedded within the egoic realm, and are able to incorporate this into the “what is” of thier lives. They are, as Ram Dass has been known to say, very much “players” in this culture.

What they also are, however, is that they have uniquely recognized and developed a deep relationship with another realm as well, the realm that Buddhist teaching points to. It is the spiritual realm that Thich Nhat Hanh describes as “the ultimate realm”, the realm that Tolle calls the realm of “Being”. These men, Eastern and Western have taken the teachings of Buddhism and other mystical religious traditions and experienced, as the Buddha and others have realized, an awakening. Awaken! This is the only message of Buddhism, Jesus, Tolle, Ram Dass or the mystical prophets of any religion.

Awaken, and embrace, not some particular Eastern religious orientation or sect, but Life, just as it is, in its wonder and perfection, even when from our personal egoic perspective, it may not seem wondrous or perfect at all. This is the only message, and when through our commitment to truth, presence, gratitude and compassion we are able to find this ultimate realm that coexists within our egoic lives, there we will also find what we are all really looking for. It is what every religion, philosophy and psychology purports as its purpose. It is the realm of personal peace.